By Carol Mowdy Bond

Contributing Writer

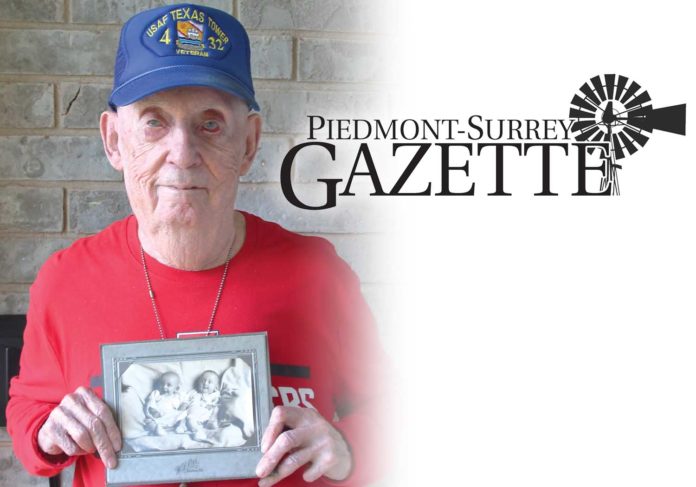

Canadian County veteran Ollie Foxhall was stationed on the Atlantic Seaboard as part of the military’s successful front line efforts to protect the U.S. from foreign invasion during the 1950s. He served in the U.S. Air Force as a radar technician for four years, and he made daily perilous climbs to the top of very high structures. As well, Foxhall was in on the ground floor as part of the U.S. Air Force’s development of AWACS.

Graduating high school in 1951, Foxhall found employment. But he knew he was about to be drafted to serve in the Korean War. He and his twin brother both volunteered for the U.S. Air Force because they did not want to be drafted into the U.S. Army.

Foxhall began with basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, then he attended electronic radar school at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi.

The U.S. Air Force stationed him in Cape Charles, Virginia, as a radar technician where he worked as a long range radar repairman as part of a repair team.

“They were long range air defense radars, looking for Russian bomber aircraft that might fly into the U.S. air space. And we had U.S. fighters on the ground, ready to take off if the Russians came. The Russians knew we had this, so they didn’t come,” Foxhall said.

The radar was on top of the tower. So, two to three times each day, Foxhall climbed a 100 feet tall tower.

Foxhall said there were other military locations, similar to that of Cape Charles, located on the Atlantic Seaboard.

“Then I volunteered to be on the Texas Tower Radar, 110 miles off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in the North Atlantic Ocean. I was still a radar technician. I lived on the Texas Tower for 1 1/2 years. The bottom of the tower was 50 feet above sea level. We had pretty strong storms, and sometimes the white caps would hit the bottom of the tower and the tower would shake. There was also one of these towers off Long Island, New York, and during a storm it blew over and killed 32 people. So they decommissioned these towers,” Foxhall said.

While living and working on the Texas Tower, “we witnessed the U.S. Coast Guard going up and down the Atlantic Seaboard in a blimp as part of U.S. security. We also saw submarines down in the ocean. And we saw ships,” Foxhall said.

Foxhall was transferred to an onshore radar site north of Boston, Massachusetts. Decorated by the U.S. Air Force for his service, his time was up in 1957, and he left the military.

The G.I. Bill paid his tuition at Texas Tech University, where he earned a four year degree in electrical engineering. “But I finished in 3 1/2 years. I took 29 to 30 hours every semester, and I studied until midnight about every night,” Foxhall said.

Degree in hand, Foxhall landed a job as an engineer with Hazelton in Port Washington, New York. Again he was repairing long range search radar. “When I first reported to Hazelton, they had a contract to build the AWACS Radar. I did some of the design work on the AWACS,” Foxhall said.

The U.S. Air Force created the Airborne Early Warning and Control System, or AWACS, as a mobile long range radar surveillance and control center for air defense, with a goal of detecting aircraft, ships, and vehicles at long ranges and perform command and control of the battle space in an air emergency by directing fighter and attack aircraft strikes.

“AWACS is a search radar in an airborne airplane. It flew all over the world. It could go to places where there was no ground radar,” Foxhall said.

From Hazelton, Foxhall moved on to Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City. He installed modifications on air force search radars all over the U.S., traveling the nation by car. He ended up at the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City, a regional office of the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, FAA, where he was the manager of the quality control branch of the logistics center which furnished electronic radar, communication electronic supplies globally to FAA installations. With other jobs that followed, Foxhall said he retired four times.

During his career, Foxhall said, “I was indirectly involved with maintenance of VOR. It’s a navigational tool for airplanes.”

The Very High-Frequency Omnidirectional Range system, VOR, is used for air navigation. VOR is older than GPS, but it has been a reliable source of navigation information since the 1960s, and is still useful for some pilots. The VOR system is made up of a ground component and an aircraft receiver component.

Foxhall grew up in Texas. He boasts that he was the first chair cornet player in his junior high and high school bands. His father was a repairman at a cotton mill gin company that made cotton seed oil.

A second grade teacher, Foxhall’s mother died when Foxhall and his twin brother were 16 years-old.

Now married for 59 years, Foxhall and his wife have two children, and two grandchildren. And Foxhall always wears three rings on a cord around his neck: his high school ring, his college ring, and his wedding ring.